Alex Spremberg vs Clare Peake

|

Clare Peake (CP): Your work seems to contrast the structural properties of the materials you use to often formal constraints or structures that attempt to control these innate qualities, but neither of these elements seems to determine the outcome of the work exclusively. It seems like the end product is mutually determined or arrived at when these two elements reach a sort of balance, perhaps a kind of equilibrium, maybe the paint might dry or the shape of the support you are using dictates an end point and you are forced to stop. Initially I thought this was a very strange and intriguing conundrum; it’s both tittering on the occurrence of a completely chaotic moment and a completely controlled or restrained one, but perhaps it is actually not that strange. When I think about it most things in life have this quality too but what is unsettling, for me at least, is having this quality be the focus of my attention. It is also what is very appealing. Does this reflect your process for making work? Alex Spremberg (AS): There seem to be two elements working with and against each other. The controlling, rational and analysing elements already appear when building the grounds that will be used for painting. Before the painting process, quite often the works are covered with a fine grid to mark the points of pouring. Since I use enamel paint straight from the can, the consistency is quite liquid and absolute control of the flowing substance is impossible. With the process of pouring the other dynamic of chance, the irrational and the chaotic enters the equation and from then on all my attention has to be in the present moment and on the unstable substances that follow their own path. Even though I have been working with these processes and materials for a while and have gained an understanding of their characteristics, the results are always surprising and every painting turns out differently than I had anticipated. I like the analogies you’re making with ordinary life and agree that we have to balance the forces of choice and chance continuously.

Perception is an active not a passive process - what we perceive is not what is out there but what we have constructed. It is about the possibility of perception without preconception. CP: I agree, we are trained to see through a “cultural lens”. To a large degree this dictates our perception or at least shapes it, perhaps we are often passive to this framework rather than are viewing passively? We constantly and actively interpret things try to make sense of the stuff around us, and this must happen from within this framework, which on the one hand can be seen as a restrictive element, but it is also what allows us to communicate and be understood through a shared language, that’s not to say it doesn’t contain variability just that it is a point of reference. I think your work uses this reference point by disrupting it or skewing it slightly. In this sense it employs our visual conditioning and then lets it fall off the grid, or maybe it allows the possibility for this to happen by using its own structure to create an anti-structure. That must sound a bit angsty, does it? I think I just mean it sits in between spaces but relies on a structure for this to happen, which also creates an unknown sort of space and the possibility for the same structure to be viewed in a new light? AS: Historically minimalist works have been a strong influence, so I find myself beginning the works with some kind of structure that will than be altered, compromised or totally dissolved. The process of working with enamel paint and its characteristic fluidity seems well suited to challenging the rigidity of a structural framework. As I am not using brushes, which are tools to control the paint, the integrity of the substances will be maintained. The act of painting is my awareness to what goes on with the paint at the moment. Sometimes I have been tilting the ground slightly to move the paint around and recently I have made even more extreme movements such as dancing around the studio while the paint is dripping off the work. I am observing the paint throughout and decide at which point I will arrest the flow by stopping my movements. The element of surprise, the incalculable or unforeseeable is very important to me and I have always tried to include it in my practice. It is like inviting forces beyond my control to be part of the process.

Traditionally enamel paints are not related to artistic practice and I have build most of my grounds from wood or MDF rather than using canvas. Other non-precious materials I have been working with are matchboxes, paper Mache, cardboard and wire. Their simplicity, familiarity, accessibility are characteristics that attract me to these materials. CP: It seems like a process that is driven by an awareness of itself, and operates as a sort of feedback loop which through isolating particular elements or interrupting this loop, a new series of unexpected consequences are instigated. It’s almost like the work materialises from a process that is controlled to do uncontrollable things... It is interesting that you say the act of painting is your awareness of what goes on with the paint in a particular moment rather than perhaps viewing painting as an awareness of the process of applying the paint. Are the works in some cases also then records of time or durational pieces that record the process of constructing the work? AS: My last exhibition at Galerie Düsseldorf in 2009 was called Million Moments. This was a reference to the many repetitive activities that resulted in the finished painting. In the work Shelf Life from 2001 I repeatedly poured varnish over a horizontal white board over a period of 18 months. The build up of the slowly drying drips of varnish resulted in Stalactite like formations at the edges of the board. Duration has always been an important component in my work. Naturally, the passing of time is a component in process-based work. I don’t have a preference for short or long durations. They simply produce different results. The paintings that I have been working on lately have to be completed before the paint dries, in order for them to work. That is within a time-span of a couple of hours, depending on the outside temperature. It also is restrictive with regard to the size of the works. Larger paintings can only be done in winter, because the paint needs to be liquid for a longer period, as more surface area is covered with paint. Therefore I have to adjust my painting practice to the conditions of the weather. There are other variables as well, that have to be taken into consideration. Not every can of industrial enamel has the same consistency, even though it has exactly the same label. At some point I noticed that older paint is more suited to my work than the fresher paint. So I was hunting for old dusty tins at the back shelfs of paint stores. What is interesting about duration is that we have fixed its measurements very precisely and our whole lives revolve around those conventions, but when we are deeply involved in an activity that all ceases to exist. Time as we conventionally use it becomes meaningless and moments can dissolve into timelessness. Published: October 2010 |

Shelf Life 2002 Varnish on wood 18 x 94 x 18 cm

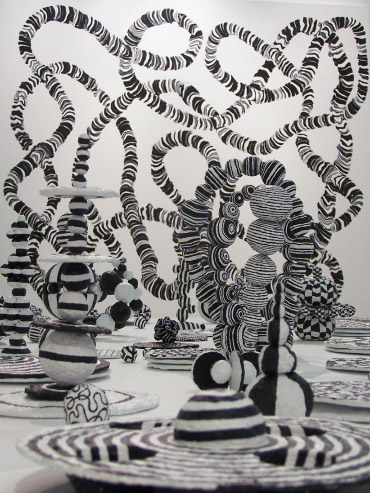

Installation of Perceptual Objects Karen Woodbury Gallery 2008

Detail: Black Twister Silver from the exhibition Million Moments at Galerie Düsseldorf 2009

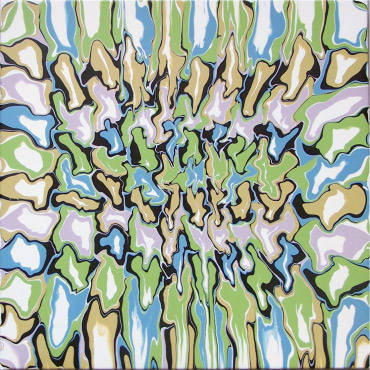

Untitled 2010 Enamel on canvas 60.5 x 60.5 x 3.5 cm |

Alex Spremberg

Born in Hamburg, Germany in 1950, Alex Spremberg immigrated to Perth, Australia in 1982. Alex currently lecturers at the Central Institute of Technology and has been a guest lecturer at Curtin University and Edith Cowan University.

Alex has regularly exhibited at Galerie Düsseldorf for almost twenty years, most recently with his solo show Million Moments in 2009. He had a survey exhibition at the Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery, University of Western Australia in 1994 Painting 1976 – 1994; as well as three solo shows at the Karen Woodbury Gallery, Melbourne (2004, 2006 and 2008).

He has also participated in numerous group exhibitions, both locally and abroad, including at the Galerie Beeld & Aambeeld, The Netherlands (2004); Goddard de Fiddes, Perth (2004); Stella A Galerie, Berlin, Germany (2004); and at the Art Gallery of Western Australia, Perth (2003).

Alex has been the winner of the prestigious BankWest Contemporary Art Prize (2004); the Artitude Prize, Telethon Speech + Hearing (2005); and the People's Choice Award, BankWest Contemporary Art Prize (2002). Among many other awards, he has also received several grants, including a six-month residency in Basel, Switzerland, awarded by the International Artists Exchange Program (2006), and the Creative Development Fellowship Grant from ArtsWA in 2007.

Alex is also represented in many prominent public and private collections across the country, including the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra; the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne; the Art Gallery of Western Australia, Perth; the Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide; the University of Western Australia, Perth; Curtin University of Technology, Perth; Edith Cowan University, Perth; Murdoch University, Perth; Artbank; BankWest; Wesfarmers, Perth; the Holmes a Court Collection, Perth, and DaimlerChrysler Contemporary, Berlin.

© The text, images and all data ('the content') of the artperth.com website are copyright. Copyright in the content of the website remains with Artperth, Artists and other copyright owners as specified.